Content note: This piece uses identity-first language (e.g., “Autistic person”) rather than person-first language (e.g., “person with autism”). In many of the communities I belong to, identity-first language is preferred—we find person-first phrasing can feel distancing, misleading, or even harmful.

Not everyone with a disability shares this view. As a disabled person, this is the language I choose for myself.

Folks, I can’t with this.

And look—I’m usually one for hopeful optimism. I try to see the nuance, to extend grace, to hold space for possibility. Heck, even my writing is usually about thoughtful contemplation with a side of controlled optimism. I want my readers to leave feeling better for having read what I wrote.

Most days, my goal is to be the ghost light in the theater—a last, little spark of life in an otherwise dark, quiet world.

But not today.

Sure, I could talk about how I played JV softball my freshman year of high school.

Sure, I could talk about the taxes my husband and I paid this year.

Sure, I could direct you to my (very VERY long) resume.

I could tell you about my poetry—including the stuff that’s been published (that I don’t talk about because I was very young and the poems feel “cringe” to me as an adult). I could tell you about my dating history. I could tell you about my (very detailed) bathroom habits.

I could tell you so many things that I have done while being an Autistic individual.

But I won’t. Why?

BECAUSE I SHOULDN’T HAVE TO.

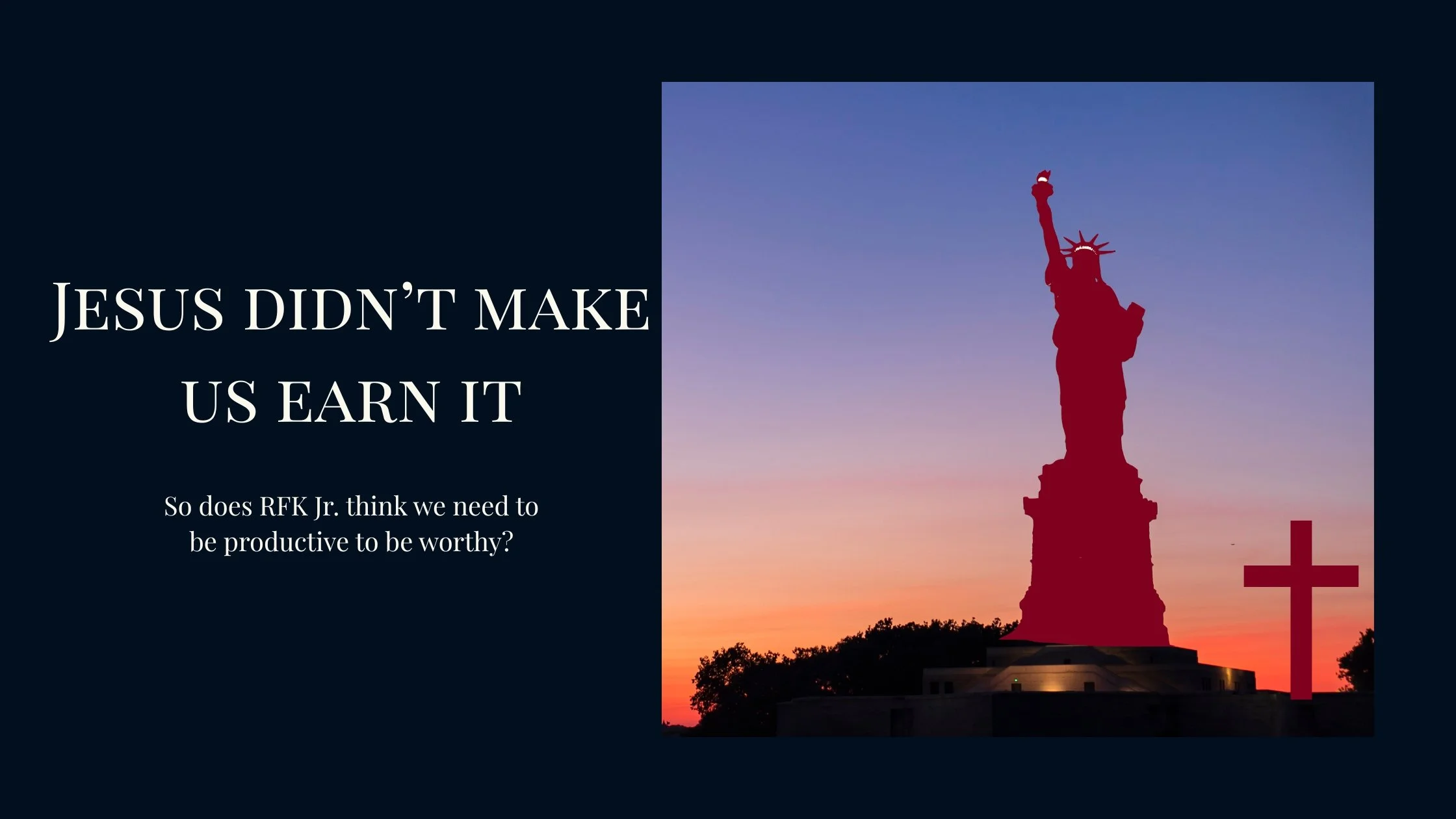

What would Jesus Do?

I’m not usually one to quote Scripture, but come on:

Jesus didn’t ask the lepers to prove their worth. He didn’t tell the poor to get a job. He didn’t avoid the sick or cast out the sex workers.

He fed them (Matthew 14:14-21). He healed them (Mark 1:40-42). He walked with them (Luke 24:13-35).

He valued them (Matthew 15:24). He loved them, and instructed them to care for others in the same way (John 13:2-16).

If that’s what Christian values are supposed to be, then we’ve strayed a long way from the Sermon on the Mount.

And while we’re at it—if you want to talk about patriotism? Let’s talk about that poem at the base of the Statue of Liberty. You know the one:

“Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free…”

That is supposed to be a promise, a promise to see worth in the people this world tries to ignore.

So tell me again why we keep deciding who deserves to live based on their (usually economic) output?

Capitalism’s Quiet Violence

People with disabilities are worthy of existence regardless of what they may or may not “contribute” to society.

Read that again. Does that make you uncomfortable? If it does, let’s unpack it.

We live in a capitalist society—yes, a mixed economy, but one where profit still reigns supreme. The government doesn’t own the means of production; individuals and corporations do. That means if we invent something, we need to find investors. If we create art, we need to find a buyer. If we want to survive, we’re expected to monetize our skills, our time, even our identities.

This isn’t just theory—it’s how the system works. And while capitalism doesn’t require devaluing disabled people, it tends to do exactly that when left unchecked. Because when profit becomes the primary measure of worth, anyone who can’t produce on demand gets cast aside.

I’m currently holding off on a minor, relatively “cheap” exploratory surgery because—no joke—I can’t afford it. Even WITH my $500/month insurance.

The fact that I had to make that kind of choice, to delay something that won’t impact me day-to-day yet but might kill me later, is an illustration of late-stage capitalism. It’s a world where everything has a price tag—and that includes people’s lives.

So, when a member of society isn’t a “productive” member? They’re ostracized at best, eliminated (in various ways of varying levels of extremes) at worst.

Capitalism, with its moral complexities, is fraught enough on its own. But when we add in the intersectionality of disability, the entire structure becomes not just broken—it becomes dangerous.

Autistic people are more than “just” what we can “contribute” to society.

The Bigger Issue

I’m heartened to see the backlash RFK Jr. is receiving, but it hurts to watch the backlash miss a bigger point.

Yes, what RFK Jr. said is factually wrong. Many autistic individuals are like me—“productive” members of society. I’m willing to bet those numbers will only continue to rise as more and more women are diagnosed and as screenings become more accurate.

But, as so many people love to say, autism is a spectrum. And I’d add: the spectrum differs from day to day.

Sure, today I can work. But tomorrow? I don’t know. Any person with disabilities knows this struggle. We know what we can do today—but we don’t know what tomorrow will bring in terms of ability.

What makes RFK Jr.’s words even more painful is knowing where this kind of discourse leads.

You may have noticed I’ve only used “Autism” to describe my neurodivergence. I haven’t used the term “Asperger’s.” Let me explain why.

Hans Asperger (b. 1906, d. 1980), for whom “Asperger’s syndrome” was named, was an early 20th-century physician who studied atypical neurotypes. His work played a large role in shaping how we understand Autism today.

He was also a Nazi. Asperger was the one who made the final call on which neuro-atypical children were to be sent to the camps and which were to be sent into the community the Nazis were “creating.” To put it bluntly: Asperger’s syndrome was shorthand for “Autistic, but they can be useful so we won’t kill them.”

If you’re still not tracking: Asperger’s syndrome came from the practice of eugenics.

Real Danger Behind Rhetoric

Folks, that is what worries me about RFK Jr.’s words. Sure, I’m an autistic member of society who does all the things RFK Jr. says I shouldn’t be able to—but that doesn’t matter.

What matters is I am human.

So is the autistic adult who has incredibly high support needs and will never earn a dollar in their life.

I know, I know. The slippery slope is a fallacy for a reason. But I’d argue there are other, quieter fallacies we don’t talk about enough:

First, we’ve fallen victim to the false premise—the idea that human worth is something you earn, that dignity is conditional. It’s baked into so many of our conversations about disability, work, healthcare, and who “deserves” support.

And then we’re guilty of the circular reasoning: we say people shouldn’t get care or support because they don’t contribute, while ignoring the fact that the very lack of care is what often prevents them from contributing in the first place.

This is Happening. Right Now.

This goes beyond theoretical, logical gaps in rhetoric. These fallacies directly feed into the moral failure of the current administration—a moral failure that has been building for decades.

The concentration camps already exist. And those parties pushing for more? They’ve never been quiet about their goals.

So the question is: who do you think is going to be next to fill those camps?

Niemöller has been quoted to death lately, but that doesn’t make his poem any less true:

First they came for the immigrants, and I did not speak out—because I was not an immigrant. Then they came for me—and there was no one left to speak for me.

This doesn’t stop. It never stops.

Not unless you grow a backbone and take a fucking stand.